Terror as Theatre

An essay on acts of violence and their relationship to surrealism, the avant-garde, and performance art (originally written in 2019)

In the Second Manifesto of Surrealism (1930), André Breton asserted:

The simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down into the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd. Anyone who, at least once in his life, has not dreamed of thus putting an end to the petty system of debasement and creullization in effect has a well-defined place in that crowd, with his belly at barrel level. (Breton et al, 2008)

Avant-garde manifestos of the early 20th century by design are provocative; arguing for revolutionary change is impossible without the use of language that evokes violence. While in the footnote for the statement above, Breton nods with a wink to his ‘own natural tendency to agitation’, this argument can be taken completely at face value to contextualise contemporary acts1 of mass terror as performative theatrical art. Surrealism, especially for Breton, concerned itself with the expression of the subconscious and automatic actions. What is an act of violence if not the most automatic expression of the darkest subconscious desires?

Surrealism […] believes, and it will never believe in anything more wholeheartedly, in reproducing artificially this ideal moment when man, in the grip of a particular emotion, is suddenly seized by this something stronger than himself which projects him, in self-defence, into immortality. If he were lucid, awake, he would be terrified as he wriggled out of this tight situation. The whole point for him is not to be free of it, for him to go on talking the entire time this mysterious ringing lasts: it is, in fact, the point at which he ceases to belong to himself that he belongs to us. (Breton et al, 2008)

Abject violence represents the apotheosis of Breton’s above definition of surrealism. Mass murderers are elevated into immortality by the notoriety gained through their deeds. Mental illness is often cited as something that precipitates these acts, echoing Breton’s statement on lucidity. These actors often have their own manifestos, using hyperbolic, florid language reminiscent of the art manifestos of Breton himself, and other early 20th century avant-garde artists. News media and the possibility for self-publishing online ensure the survival of their memory, satisfying art’s need for archival safeguard, as argued by Boris Groys. (For the sake of brevity, I will focus on the phenomenon of mass shootings in the West, with acknowledgement of the inherent limitation in scope, especially reflecting the global world of today.2)

THEATRE & THE AVANT-GARDE

Groys defines the basic spirit of the avant-garde as a ‘demand that art move from representing to transforming the world’ (Groys, 1992). Theatre was an important medium for the Russian avant-garde because of its ability to synthesise artistic practice with ideology in a didactic form. The political and the aesthetic were inseparably intertwined in an ‘aesthetico-political discourse in which each decision bearing on the artistic construction of the work of art is interpreted as a political decision, and, conversely, each political decision is interpreted according to its aesthetic consequences’ (Groys, 1992). By combining contemporary interpretations of set design, costume, music, and playwriting, theatrical productions of this period represent an extension of the idea of the gestsamtkunstwerk introduced by Wagner in Art and Revolution and The Artwork of the Future (1849). An obvious progenitor of this concept is the Christian mass and the architecture and interior of churches.3 (These ideals extend into the fields of interior design and architecture, but for the purposes of this paper I will consider only their performative manifestations.)

Groys also argues that ‘in avant-garde art that we find a direct connection between the will to power and the artistic will to master the material and organise it according to laws dictated by the artists themselves, and this is the source of the conflict between the artist and society’ (Groys, 1992). This ‘will to power’ is important in the consideration of the mass shooting as a performative artistic act. There is perhaps no greater expression of power than taking the life of another (or oneself); it is the only truly irredeemable act. In the progress of art from the 20th century until now, traditional modes, such as oil painting on a canvas or sculpting in clay, have been increasingly dematerialised to the point at which an idea can constitute an artwork. In contemporary times, the exhaustion of all forms of traditional artistic expression lead logically to an aestheticised performance of living constituting the ultimate artistic act.

According to Benjamin Noys, ‘the transformation of politics and the world into an aesthetic matter neglects the ways in which artistic practice engages with its material, and offers a politics that is driven by an irrational celebration of powerful images’ (Noys, 2018) which signifies the dematerialisation of art into the image-mediated reality we live in today, where images of violence are arguably the most powerful. In Adam Curtis’ documentary Hypernormalisation (2016), Curtis suggests that Vladislav Surkov, advisor to Russian President Vladimir Putin, imported ideas from conceptual art into politics to create a kind of ‘bewildering, constantly changing piece of theatre’ that has served to undermine people’s perception of reality to maintain control. (Curtis, 2016) This idea of politics as theatre can be extended into the concept of all contemporary life as theatre, which is especially relevant when considering that the proliferation of social media asks that everyone not to be themselves in a localised social group but perform themselves for a (potentially) global audience of followers.

EVOLVING PERFORMANCE

While early 20th century theatre was distinctly collective, performance art in the 1960s and 1970s shifted toward centering the artist as an individual, while also considering audience participation as a vital aspect. This shift can also be seen as a signifier of the continuing cultural shift from the collective to the individual, and the political shift from communism to capitalism. The cult of personality surrounding artists, while by no means a new phenomenon, has followed this shift in a way that can be seen in parallel with the notoriety of mass shooters. Total works of art realised in the theatrical mode imply a distinct separation between performer and audience. Materially, an interior space with a clearly designated stage and seating area enforces this separation. Ideologically, the didactic intention of Russian avant-garde productions indicates the assumption that the audience passively apprehends the work presented before them. This separation also implies a certain protection of audience members; they are abdicated from any responsibility other than observation in the immediate context. For the mass shooter as artist, the participation of audience is absolutely imperative for the performance of the work. Any trace of a barrier between performer and audience is dissolved by force.

In Marina Abramović’s iconic performance Rhythm 0 (1974), a table was set with 72 objects, ranging from innocuous items, such as perfume or honey, to items with more potential for harm, such as scissors and nails, and a pistol loaded with a single bullet. In the instructions for the performance, Abramović importantly designated herself as an object as well. The gallery space notably did not establish any hierarchical structure separating Abramović from the audience members who were invited to use the objects upon her as desired. She was not elevated from the audience on a stage or plinth but rather occupied the space at an equal level. The work was intended to invert the relationship between the performer and the audience in response to critics who denounced performance art as exhibitionism or masochism. In a 2013 video on the piece, Abramović says she sought to interrogate ‘what is the public about and what will they do in this kind of situation’ (Zec, 2013).

During the six-hour performance, acts of increasing violence transpired; her clothing was removed, she was sexually violated, and her body was cut in various places, including the throat. An audience member placed the loaded pistol in Abramović’s hand with her finger on the trigger, which prompted guards at the gallery to take action. For the duration of the work, she maintained her role as an object, remaining motionless, ‘like a puppet’ without reaction to the events taking place. When the performance finished, she began to move as herself and the audience abruptly left, unable to face her as a real person (Zec, 2013). This reversal of performer and spectator is important in that the existence of the audience becomes essential in the activation of the work, but it also illustrates the banal capacity for cruelty that is perhaps inherent in every person. By presenting herself as an object, Abramović introduced an alienated relationship between herself and the audience potentiating her own dehumanisation.4 It is a similar underlying alienation and objectification that allow perpetrators of mass shootings to act in a way that totally subverts societal norms. The dehumanising violence enacted upon a body to render it lifeless transforms a living being into an object. Further, after the act, a mass shooter must be subject to a process of othering by the general public to avoid considering the fact that the capability for extreme violence is present in human nature.

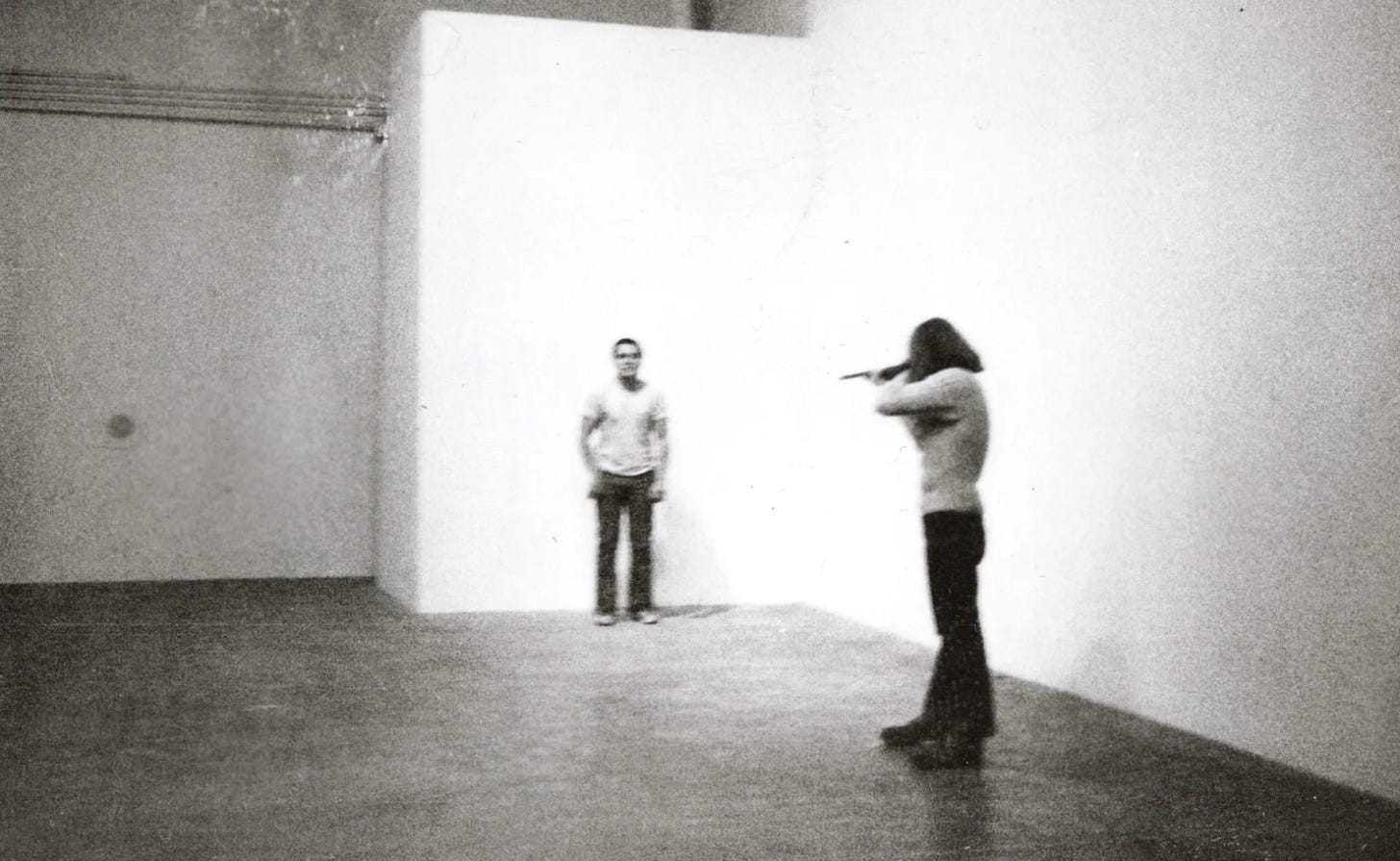

In Chris Burden’s conceptual performance Shoot (1971), the artist recruited a friend to shoot him in the arm. Burden conceived this piece in response to the Vietnam war, in which many of his contemporaries were forced to participate, and which resulted in images of violence dominating televised media (New York Times, 2015). This piece as a reaction to circulated images introduces an important relationship to the mass shooting as reaction to the ever-increasing barrage of violent images appearing today. While in the 1970s, television was the primary source of this content, today the Internet provides a readily available, infinite archive of abject violence. It is easy to see the potential connection between perpetrators of mass shootings consuming these images and reacting in a capacity of reproduction. Artistic production does not exist in a vacuum; it is always a product of cultural and societal contexts.

While Burden and Abramović expressly created works with artistic intentions, one of the most infamous events in the history of contemporary art is more ambiguously intentioned but obviously aligned with the canon of performative violence. Valerie Solanas’ SCUM Manifesto (1967) and subsequent shooting of Andy Warhol and Mario Amaya introduce the potential to read an act of violence as art without the creator explicitly defining it as such. Though Solanas acted within the sphere of the New York art scene of the 1960s, her status as an outsider and her subsequent diagnosis of mental illness serve to obfuscate the distinction between art and non-art.

THE INTERNET & DEMATIRIALSATION

In Dangerous Artists of Calibre: shooting people as performance art, Martin Lang concludes ‘Breton’s call to shoot randomly into a crowd cannot be accepted as art.’ Lang cites the institutional theory of art developed by Arthur Danto and George Dickie, ‘for something to be art, it must be accepted as such by an “artworld”’ (Lang, 2018). However, when assessing this theory in the contemporary context, the coherence of the so-called artworld has been profoundly interrupted by the Internet. Because the Internet has fundamentally altered nearly every aspect of life today, especially when considering the proliferation of visual media, this theory seems deeply outmoded. As Groys states, ‘the Internet gives to everybody the immediate possibility to present oneself on the global stage–everybody makes selfies, videos, writes blogs, and so on. We no longer have a mass culture of consumers–the situation that was described by Adorno–but a situation of mass cultural production, where everybody is an artist, everybody is a writer, and a philosopher’ (Lijster, 2018). The Internet vitally allows the criteria for identifying an artist to become completely subject to interpretation. Either everything is art, or nothing is. This liberation of artistic identity signifies that there is nothing to materially separate an artist from a non-artist. In this way, the mass shooter can be considered as much an artist as not.

In the same interview, Groys discusses archival spaces, such as museums, as the basis of culture. Acts of creation are facilitated by ‘instinctive trust’ in these institutions’ power to preserve designated items for the future. However, the Internet has assumed an archival function that is far more nebulous than institutional archives of the past. Where once there was some sort of authoritative evaluation of what cultural productions were worthy of preservation, the Internet is an indiscriminate receptacle for user-generated content. The Internet also functions to disseminate this content without curatorial consideration, but yet it is impossible to consider that the Internet does not function as an exhibition space, despite the fact it lacks a coherent structural logic in doing so.

SELECTED CASES

The Christchurch mosque shooter (2019) used Facebook to livestream his attack, thus further documenting the performative nature of the act and ensuring its preservation in the digital archive. The 17-minute video begins with the shooter driving to the scene of the attack and ends with him returning to his car and speeding away, thus constituting a logically complete documentation of act. (NZ Herald, 2019) The use of livestreaming shows a deliberate engagement with a perceived audience, a level removed from the victims who are perhaps not only forced to become a participatory audience but also performers as well, not unlike Rhythm 0. The attack also featured distinctly theatrical elements including playing ‘a British grenadiers march and a Serbian anti-Muslim hate anthem’ and embellishing weapons with ‘white lettering, featuring the names of others who had committed race- or religion-based killings; Cyrillic, Armenian, and Georgian references to historical figures and events; and the phrase: “Here’s Your Migration Compact”’ (Doyle, 2019). This shows deliberate aesthetic choices, thus rendering this act perhaps materially indistinguishable an artistic performance. His manifesto, published online and directly sent to media outlets, detailed his ideological basis for carrying out the attack, not unlike a press release issued prior to a performance or theatrical production.

Similarly, the Columbine shooting (1999) was highly stylised. The black trench coats worn by the shooters were culturally reviled in the aftermath, becoming a symbol of the shooters. The act was preceded by creative production by the pair, including writing and videos, indicating the shooting was not merely an act of violence but a logical conclusion to an aesthetic ideology they developed. In a 1998 video, Hitmen for Hire, the pair dress in outfits nearly identical to the ones they wear when later perpetrating the shooting and act as hitmen offering protection to other students from bullies, including their contracted murder. During one scene, Klebold repeatedly breaks character to laugh during a vitriolic monolog delivered to the camera (Harris and Klebold, 1998). The film reads as eerie in its foreshadowing of the tragic events to come5, but at the same time it doesn’t seem out of place for a high school film making project authored by someone with a slightly macabre sense of humour. After all, nerds seeking revenge on their bullies is a ubiquitous trope in American television and film.

CONCLUSION

Avant-garde art of the 20th century, conceptual performance art, and mass shooters all share a history of being heavily criticised, denounced in the press, and rejected by the public while also achieving a distinct notoriety only possible through shock and provocation. The phenomenon of the media covering mass shooters’ abject deeds has been cited as an issue by academics and activists alike who claim it inspires imitation (Meindl & Ivy, 2017). However, in an attention economy, as theorised by Herbert A. Simon, it is undeniable that the most shocking and appalling stories receive the most views and clicks. This concept in itself has been fodder for contemporary art, including Andy Warhol’s Death and Disasters series and in John Waters’ cinematic oeuvre. At the same time, to achieve what is measured as success today, an artist must manipulate the media to gain publicity. For example, Damien Hirst gained fame and fortune for works like The Physical Impossibilities of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991), which both had a viscerally repulsive quality (the decaying shark) and drew criticism for being a gauche attempt at existentialism. Arguably, part of Hirst’s success has been due to creating media controversy as opposed to critical acclaim.

The manifestos of many mass shooters reflect extreme ideologies deemed reprehensible by culturally hegemonic standards, however reactionary responses to societal upheaval can be seen in avant-garde manifestos as well. While the avant-garde reacted to industrialisation and technological advancement, the context was still localised, and provocation was simpler. Their actions were not pushed to abjection as in the case of mass shooters. In the post-Internet, globalised world, with its ceaseless media coverage and oversaturation of images, distinctions between the virtual and the real become less and less clear. Thus, extreme escalation is perhaps only logical. In this context, these acts can be regarded as the apotheosis (but also perhaps ultimate perversion) of the gestsamtkunstwerk as envisioned by the avant-garde.

Footnotes

REFERENCES

Breton, A., Seaver, R. and Lane, H. (2008). Manifestoes of surrealism. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Groys, B. (1992). The Total Art of Stalinism: Avant-garde, Aesthetic Dictatorship, and Beyond. Princeton University Press.

Allison, R. (2002). 9/11 wicked but a work of art, says Damien Hirst. Retrieved from https://www.theguardian.com/uk/2002/sep/11/arts.september11. [Accessed 9 Dec 2019].

Lijster, T. (2018). The Future of the New: Artistic Innovation in Times of Social Change. The Museum vs. the Supermarket: An Interview with Boris Groys. Valiz, pp.116-139.

Bergande, Wolfram. (2014). The creative destruction of the total work of art. From Hegel to Wagner and beyond.

Curtis, A. (2016) Hypernormalisation (BBC).

Milica Zec, Marina Abramović Institute. (2013) Marina Abramović on Rhythm 0 (1974). Retrieved from

[Accessed 7 Dec 2019].

New York Times. (2015) Shot in the Name of Art. Retrieved from

[Accessed 7 Dec 2019].

Noys, B. (2018) The Future of the New: Artistic Innovation in Times of Social Change. Accelerationism as Will and Representation. Valiz, pp. 84-97.

Lang, Martin. (2018). Dangerous Artists of Calibre: shooting people as performance art. 94-103.

NZ Herald. (2019) Mosque shooting: Shooter describes himself and his plan in [WWW Document]. Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20190315025827/https://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=12213076 [Accessed 9 Dec 2019].

Doyle, G. (2019) New Zealand mosque attacker's plan began and ended online [WWW Document]. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-newzealand-shootout-internet/new-zealand-mosque-attackers-plan-began-and-ended-online-idUSKCN1QW1MV [Accessed 9 Dec 2019].

Harris, E. and Klebold, D. (1998). Hitmen for Hire. [online] Retrieved from

[Accessed 9 Dec 2019].

Meindl, J. N., & Ivy, J. W. (2017). Mass Shootings: The Role of the Media in Promoting Generalized Imitation. American journal of public health, 107(3), 368–370. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2016.303611

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Fatimah Alajaji, Sarah Cuk, and Chris Wright for their insightful feedback during the writing process. I also would like to acknowledge the exhibitions Russian Avant-garde Theatre: War Revolution and Design 1913 – 1933 (18 October 2014 – 15 March 2015) at the V&A in London and RED: Art and utopia in the land of Soviets (20 March 2019 – 1 July 2019) at the Grand Palais in Paris for being formative influences on my research interests.

I have deliberately chosen to refer these occurrences as ‘acts’ in line with their contextualisation as performance, though they are also sometimes referred to as ‘events’ in the discourse. It was my intention to analyse ‘act’ versus ‘event’ in a semiotic framework, but this ended up being beyond the scope of this paper in its present iteration.

Here I would like to note Damien Hirst’s 2002 comments to the BBC Online: ‘The thing about 9/11 is that it's kind of an artwork in its own right. It was wicked, but it was devised in this way for this kind of impact. It was devised visually.’ He, of course, later apologised for this statement, but I feel he was making an important point, especially in regard to how these attacks changed our ‘visual language.’ (Allison, 2002)

According to Bergande’s (2014) reading of The Artwork of the Future, death remains the last resort of the total work of art. His reading of Wagner in a Hegelian context is of pertinence here, and thus deserves a mention, but beyond the scope of this paper in its present iteration.

The designation of artistic performance and the gallery space it was presented in contextualised the work in a way which arguably could have escalated the violence. However, with the assumption that the Internet has made everything art, and because art inherently requires an element of provocation, it logically follows that art must increase in shock value.

This is especially prescient as the shooters targeted ‘jocks’ in their attack, while reportedly sparing the life of a fat student because he was clearly not a jock.